On Exile

Considerations on Dante, Caetano Veloso, Jason Stanley, and me

This essay came out of a conversation with Santiago Ramos about the theme of exile and departure, but mostly about our love of Tropicália.

Am I an exile? I left Baltimore, the city of my birth, when I first went away to college and never really returned. And I’ve now lived the majority of my adult life in one of several different foreign countries (as I still do today). Consequently, I find myself occasionally longing for home, even as its true direction becomes less certain every year. And this feeling becomes especially acute during the week of America’s Independence Day, as those around me are celebrating Canada Day—which has always struck me as a somewhat ersatz holiday by comparison.

In any case, I thought of the exile question upon seeing the news of the impending arrival to my present city of another American émigré: the former Jacob Urowsky Professor of Philosophy himself, who quite publicly announced his intention to depart what he viewed as an increasingly hostile and authoritarian United States for its northern neighbor. In a rather bombastic press release, his agent (presumably) links him to a grand tradition of political refugees escaping tyranny—not least his (and my) Jewish ancestors: “Jason Stanley—Yale philosopher, son of refugees who fled fascist Europe…just left the United States for Canada.”

The high seriousness of the themes evoked here married to the hyperbolic language of marketing can only result in farce. And yet there is something fitting about it. As Horace wrote, “Whoever, by becoming an exile from his country, escaped likewise from himself?”

Now, Jason Stanley is an admittedly ridiculous figure, and he is probably not an ideal representative of the pathos of exile. History furnishes no shortage of candidates for that position, though my own nomination would be Dante, expelled from his beloved Florence, and who even now reposes in a tomb in Ravenna. (There is some irony in the fact that the two cities are but a few hours’ distance by car—thus does modernity banalize everything.)

In lines that he gives to an ancestor whom he encounters in the Paradiso, Dante writes:

You shall leave everything you love most dearly: this is the arrow that the bow of exile shoots first. You are to know the bitter taste. of others’ bread, how salt it is, and know how hard a path it is for one who goes descending and ascending others’ stairs.

What more is there to say, really? And yet, there is a great tradition of exile literature that continues to the present day. The upheavals of the 20th century in particular generated a great swathe of it around the world: Hannah Arendt, Stefan Zweig, Thomas Mann, Salman Rushdie, Mircea Eliade, Milan Kundera, Wole Soyinka—the list goes on.

As that same list indicates, the experience of exile did not dull their literary faculties but honed them. Or, as Vladimir Nabokov wrote in his astonishing memoir, Speak, Memory: “Suddenly I felt all the pangs of exile… Thenceforth for several years, until the writing of a novel relieved me of that fertile emotion, the loss of my country was equated for me with the loss of my love.”

And of course, as Nabokov’s career demonstrated more than most, exile may confer other benefits, not least that of new languages, a gift to many a writer. Edward Said (another exile) has described them as “writers unhoused in or dislodged from any single language”

Said incidentally represents one of the curious ironies of the exiled figure: that the homeland he longs for (in his case, Palestine) is one he participates in creating. After all, how many nationalisms are engendered in exile? Giuseppe Garibaldi dreamed of Italian unification in America, Mohandas Gandhi envisioned Hind Swaraj in South Africa, Theodore Herzl convened the first Zionist Congress in Switzerland. And then there’s Lord Byron, whose exile from one country (England) inspired him to die for a nationalist cause in another (Greece). Nor should this surprise us: for from a distance, they can see a vision of unity and purpose where those on the ground only see a blooming, buzzing confusion—much the way astronauts can see the Earth as a serene whole in a way that we on the ground never can.

Meanwhile, not all exile is the result of forced expulsion. James Joyce’s exile, for example, was self-imposed, and among the many remarkable details in Richard Ellman’s remarkable biography is both how clear and precise was Joyce’s recollection of Dublin, and how he feared that revisiting the city would mar the clarity of that memory. And one understands how he felt. Whenever I do physically return to the places of my past, the memories hit with dizzying force, unadulterated by the familiarity of daily life that might have overwritten them had I remained there.

But whether we physically leave or not, we are always removed from the past—in a state of exile from our former selves. As the great French Romantic writer François-René de Chateaubriand wrote at the outset of his memoirs, “On leaving my mother’s womb, I underwent my first exile” (the subsequent ones would prove more literal).

Much the same goes for the other direction as well. Montaigne famously wrote of how we are impelled by fear and desire into the future and away from the appreciation of the present: “We are never at home, we are always beyond.” Our dislocation, then, is both spatial and temporal, and even those who avoid the former cannot escape the latter. I suspect it is partly for this reason that exile literature holds fascination for those who have not shared in such experiences.

When we speak of the pain of exile, the sense that it is an undesirable state, we implicitly mean that our natural condition is heimisch, that we long for rootedness. Simone Weil states as much in her aptly-titled The Need for Roots, “To be rooted is perhaps the most important and least recognized need of the human soul.”

While not necessarily false, I do wonder how true it is. For, surely humans are as much a wandering species as a rooted one. It was not, after all, by sticking around that we disseminated our species across the globe, mastering every biome. From the migrations out of Africa, to the flight across Beringia and subsequent conquest of the Americas, to the Polynesian odyssey from Asia over the South Pacific, to the Yamnaya invasions and spread of Indo-European languages.

And since then, it was the great maritime explorers that crossed the Atlantic just as the central Asian pastoralists yoked Asia with Europe both through trade and imperial conquest (and what is the Eurasian Steppe but a vast sea of grass?). The concept of “exile” would have been meaningless to them; it relies upon a norm of fixity.

Perhaps for this reason the theme of exile is so strongly present in classical history; just as the ancient Greeks and Romans were the citizens par excellence, so was banishment and the stripping of citizenship a particularly significant punishment.

Following his exile from Athens for the crime of impiety, the pre-Socratic philosopher Anaxagoras died of starvation. Cicero’s exile proved temporary, but he never recovered the political influence he once wielded and ultimately lost his life. The poet Ovid, who remains one of our greatest sources of classical mythology, was exiled to the Black Sea by the Emperor Augustus for reasons that remain mysterious, and the poems he composed in the final years of his life were lamentations of his fate.

This is not to say that the prevailing understanding of exile was simply tragic. Herodotus tells a highly amusing story of a group of Egyptian guardsmen who deserted their posts for Ethiopia. When the Pharaoh sought to remind them of their obligations to their wives and children, one of them pointed obscenely to his manhood and replied that wherever that was, he could always acquire more of those.

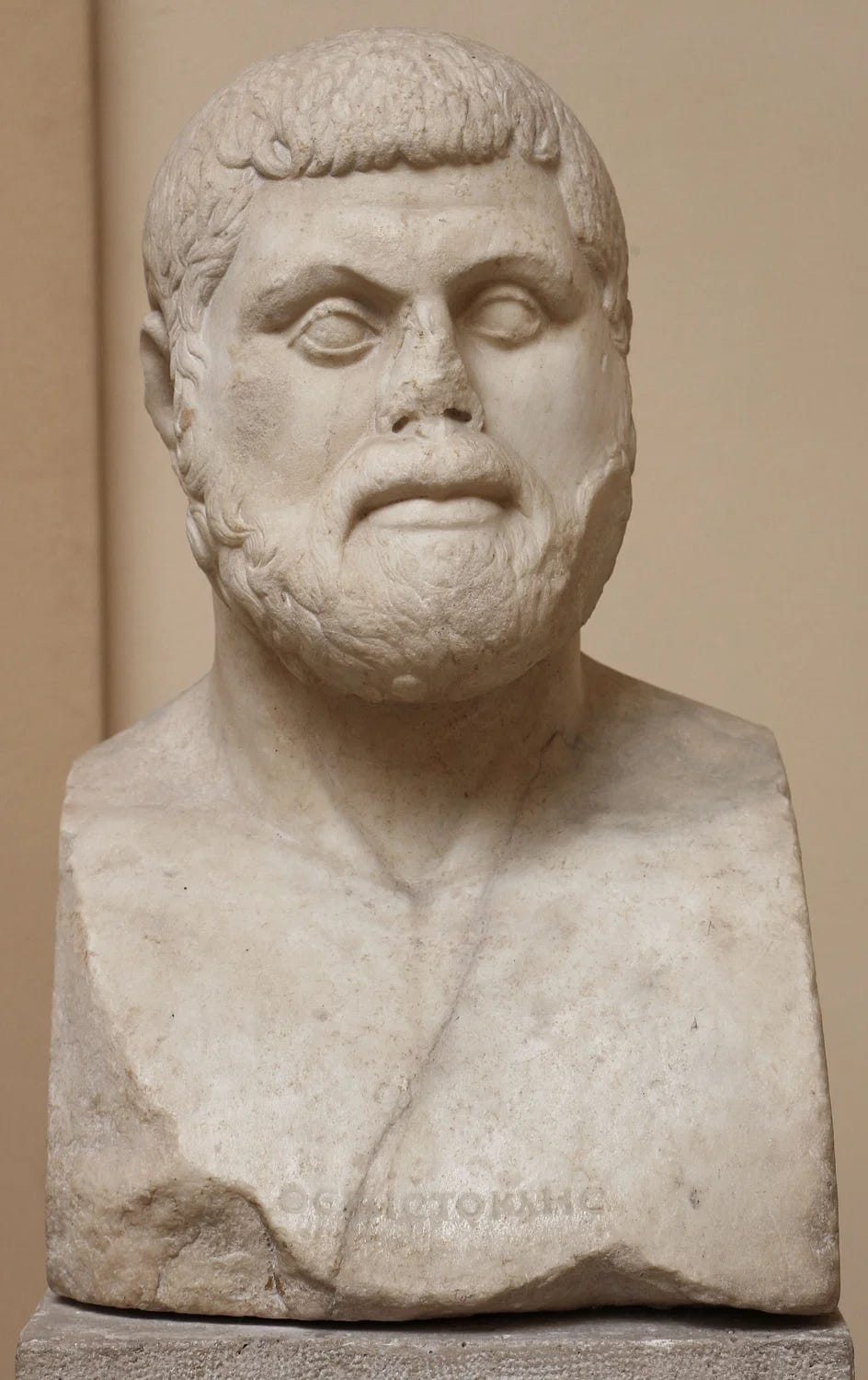

In a similarly comic vein, Thucydides tells us of the later career of Themistocles, hero of Salamis and savior of Athens. Having been ostracized for the crime of being too awesome (basically), he made contact with his former enemies, the Persians, pledging friendship and requesting asylum. Such was his genius that he quickly ascended to a high position in the imperial bureaucracy and quite comfortably lived out the rest of this days there.

Yet even so self-sufficient a figure as Themistocles longed to be returned to his native soil upon his death, and—in a final comic turn—he made provisions for his remains to be conveyed back to Attica, in violation of Athenian laws.

Thucydides himself was an exile, of course—banished by a fickle demos after being outfoxed by the wily Spartan commander Brasidas at the Battle of Amphipolis. In his typically unsentimental (though not unfeeling) way, he records this event with a single laconic sentence: “It was also my fate to be an exile from my country for twenty years after my command at Amphipolis; and being present with both parties, and more especially with the Peloponnesians by reason of my exile, I had leisure to observe affairs somewhat particularly.”

Though he would not be so trite as to state this outright, it should be obvious that the “leisure” afforded by his exile was a sine qua non for composing his history of the war. And in a higher sense, the extraordinary sense of objectivity that he displays throughout the work—what Nietzsche calls the “impartial knowledge of the world”—could only have been achieved once he left Athens (it is hard to gain a position of objectivity on a great power war when you are serving as a general for one of the principal combatants). This is to say that the misfortune of banishment was ultimately liberating. Or, more bluntly: no exile, no book.

There is of course something vulgar about treating misery as the precondition for art. But this theme has a way of making the relationship particularly stark. For, exile literature is not just literature about the condition of exile but literature that is the result of the condition of exile. Whether or not their makers would have created other works under happier circumstances, it is still fair to say they would not have created these works, and so our own perspective must include a measure of gratitude for their trials whether they share that gratitude or not.

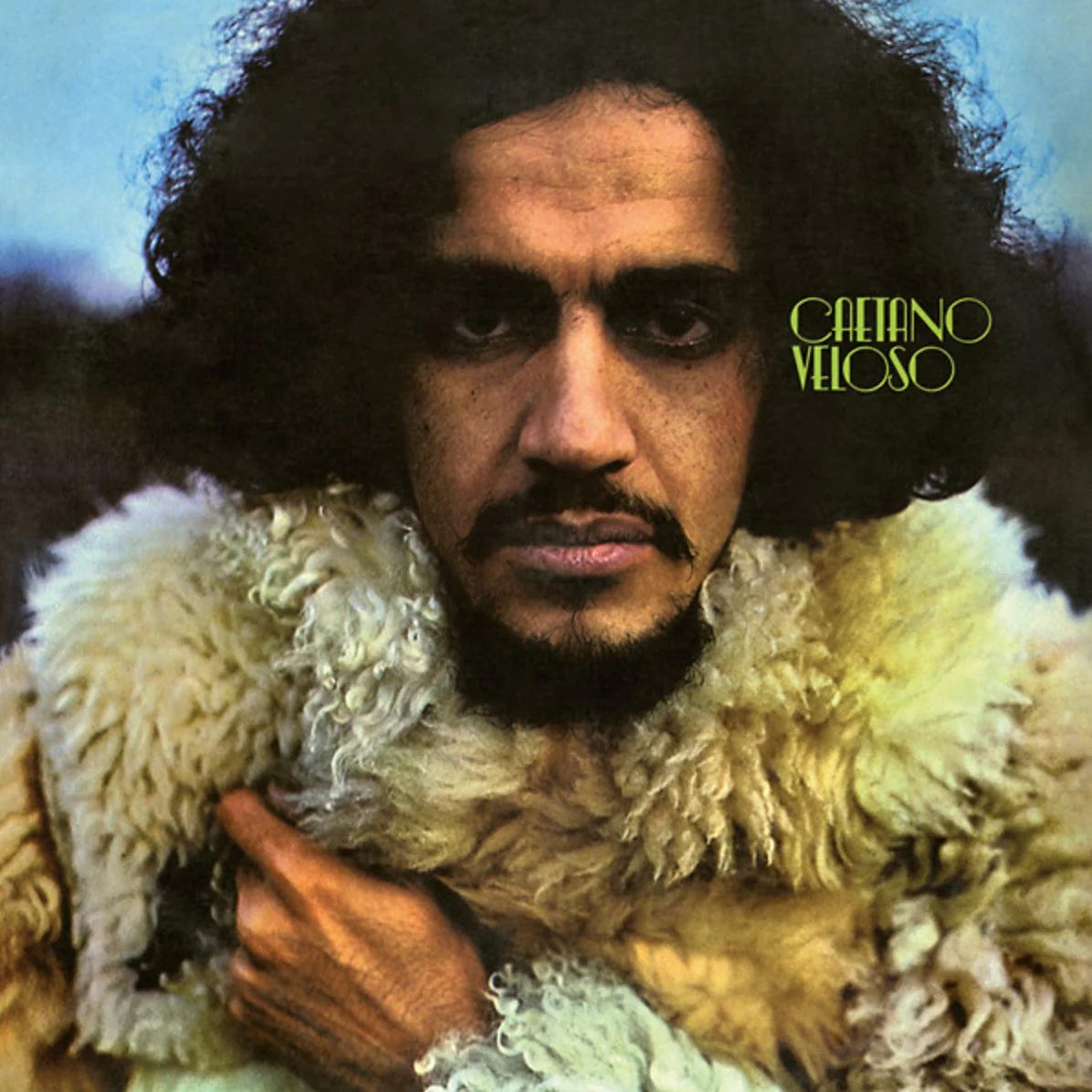

And they mostly do not. One of my favorite popular musical artists is the uncategorizable tropicalista Caetano Veloso. And perhaps my favorite of his albums is his self-titled 1971 LP, which is another way of saying that this is one of my favorite albums, period. This record is sometimes referred to as “A Little More Blue” for several reasons. First, as it is the title of the eponymous first track. Second, to distinguish it from two of his earlier self-titled (also brilliant) albums.

But the other reason it goes by this name is because it so purely captures the pensive, downcast mood that pervades it. This mood was due to the conditions of its recording in London, following his exile by the military dictatorship then in power in Brazil. (Incidentally, his compatriot and fellow musician Gilberto Gil claims to have had a perfectly wonderful time abroad.)

As though accepting the imposition of a foreign language as part of his sentence, Veloso sings mostly in English on this album, and the dazzling wordplay for which he is customarily known gives away to an oddly affecting and more childlike lyricism. Lacking the same verbal facility in this language, he displays his desolation more nakedly, unable to hide behind his considerable poetic gifts.

For me, the album’s defining track is the one that closes the first side, named after his sister Maria Bethânia, herself a major singer (and it is appropriate in this context of exile to address a song of devotion to a family member rather than a romantic partner). The song features the arresting opening line: Everybody knows that our cities were built to be destroyed.

But what sounds upon first listening as an expression of terrible resignation now seems to me to be one of perverse hope. Whether Rio or Dublin or Florence or Athens: perhaps it is better not to imagine them standing indefinitely against the ravages of time, as we long for them in exile. Like us, even the conditions of our longing will one day pass away. And, as with exiles, we return to them in art, in music, in the pages of old books.

Nothing even remotely like what you quote comes from my publicist or agent. It’s obviously something Chat-GPT generated.