Over three decades ago, Francis Fukuyama published his famous End of History and the Last Man, in which he declared that history (or rather, “History”), meaning an unfolding process of clashing ideas, was winding down and predicted a future of increasing peace and comfort if not excitement. The part of the title that preceded the conjunction was basically redacted Hegel and the part following the conjunction basically redacted Nietzsche, with the book itself being an uneasy marriage of the two.

But it was largely the first part that attracted most of the attention and criticism despite the second being in many ways more interesting. For, it gave a minor-key modulation to what was otherwise perceived as a triumphant theme. The end of great conflicts over fundamental questions about social organization would also represent the end of a certain element of greatness and striving within the human spirit, and the future would thus be an ambiguous one from a human standpoint.

He somewhat notoriously gave himself an out in the book’s final chapter, however, which was titled “Immense Wars of the Spirit.” That title is a reference to Friedrich Nietzsche’s claim that as meaning leached away from modern society, the Europeans would engage in wars “whose only purpose was to affirm war itself.” The gist for Fukuyama is that the sheer dreariness and banality of existence at the end of history (and perhaps the proliferation of last men-types) would trigger an intense if nihilistic reaction.

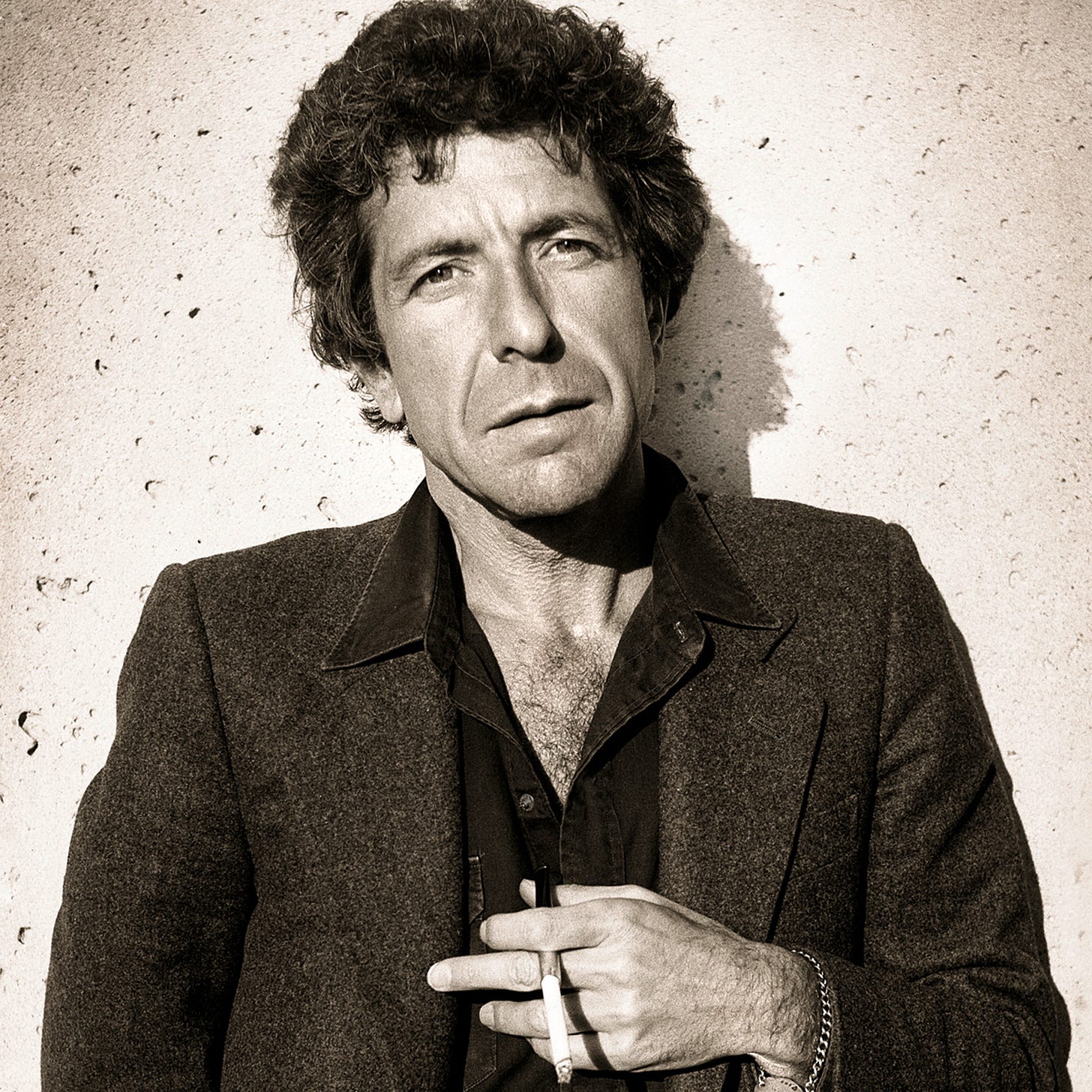

Three years after the fall of the Berlin Wall and one year after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the saturnine Canadian songwriter Leonard Cohen beautifully captured this sense in a song called “The Future,” which included the following stanza:

Give me back the Berlin wall

Give me Stalin and St. Paul

Give me Christ

Or give me Hiroshima

Cohen’s vision of the future was a slow death march – a society without the will to sustain itself, and his terse summation of the 20th century illustrates those immense wars of the spirit (now a matter of perverse nostalgia) as well as anything else.

What then do we have today? The political ascendance of Donald Trump and the overturning of what were formerly seen as liberal institutional strongholds—along with broader geopolitical shifts—have led to claims that we are seeing some sort of resurgence of that old black magic, a revival of true ideological clashes. Or perhaps just nihilistic reactions on some grand scale. And I’m sorry, but either way I just don’t see this at all.

This reality is partly obscured by our continued usage of conventional political terms irrespective of their exactness. I have mentioned before the need for a “rectification of names” when it comes to our political language today. This was an old Confucian precept that held that the failure of our language to adequately describe social conditions was a cause of disorder. Whether that’s ultimately true or not, I think it is still good for us to be able to speak and think clearly about political phenomena.

Take for example, the political right and left today. Now, strictly speaking, these categories aren’t eternal. They postdate the French Revolution, reflecting a divide between those who sought to secure and extend the new ideas of political and economic equality and those who wished instead to preserve or restore the privileges of the elect few.

One can view this dispute as merely our modern iteration of the classical schisms between oligarchs and democrats (i.e., the few and the many). But the important difference here is that no one back then viewed this divide as erasable in principle. There would always be rich and poor, and much of public life would reflect (and be fought over) the distribution of political privileges among these factions.

But modern politics went much further in its belief in the possibilities of permanently erasing inequality, and much of the political history of the past two centuries revolved around negotiating the extent of that erasure—and by negotiating, I mean wars and revolutions and great power conflicts. And it was these dynamics that shaped the major political events of the past several centuries, as new states were established and older ones sought to retain their authority, and both became venues for ideological disputes involving the protection of fundamental rights and the ownership of capital. And one’s positioning along the left-right spectrum was conditioned by one’s positions on these matters.

Fast forward to today: what is the span of that spectrum (or circumference, for those who think it as circle), and what does it even mean to be on it?

On the left, the two dominant causes right now are Palestine and Trans Rights. It’s not that these are commensurate issues or that they are without any significance whatsoever. The point is first that they have already been gathered together under the standard of the Omnicause, and second that both themes loom large among the concerns that presently animate what exists of the global Left. I think this is relatively uncontroversial. The trouble is that these are, historically-speaking, relatively niche causes that are now expected to bear the weight of expectations once assigned to more globally ambitious goals.

Even if one wholly accepts their justness and necessity, they represent at best the extension or covering off of past movements: more complete realizations of civil rights (in the trans case) or decolonization (in the Palestinian one).1 Suffice it to say that this represents a significant contraction of the historical ambitions of the political left—e.g., bringing about a global proletarian revolution.

Now, to some extent, this isn’t exactly new. The remarkable postwar economic growth in both North America and Europe posed a problem for the traditional Left, which was committed to the position that capitalism was inherently exploitative. But this proved a harder sell during a period of general prosperity.

To put it simply, too many would-be proles were more interested in putting pink flamingos on their new lawns than in overturning capitalism. Meanwhile, the extravagant hopes for the Soviet Union foundered in the wake of Khruschev’s revelations about Stalinism. By the 1960s, few young people would have called it the “moral top of the world,” as Edmund Wilson once did. The more radical (and, it must be said, in many cases mentally unbalanced) numbers among them turned increasingly to terrorism and sabotage, none of which acts had a hope of generating large-scale revolution.2 (It is partly due to the failure of both propaganda and violence to generate proletarian class consciousness that post-Cold War leftists increasingly turned their hopes to the lumpenproletariat.)

But if the left has been unable to reconstitute itself in a way that finds broad appeal since the end of the Cold War, the right had long ago thrown in the towel. The experience of WWII basically curtailed the acceptable limits of right-wing politics in a great many countries for obvious reasons. And while there were and are “right-wing” regimes, few of these were constituted according to any meaningfully anti-liberal philosophy, not least because they were obliged to accept certain material realities (e.g., a leader like Salazar in Portugal still ended up committing himself to the same program of modernization as any Fabian socialist).

Within the United States, meanwhile, conservatives tended to accept the constraints of their own liberal democratic regime—i.e., the thing they were almost invariably conserving was some older, more “traditional” version of democracy. And to the extent that their vision was at odds with that of the more liberal mainstream, they were able to establish viable counter-institutions that largely had the effect of moderating their own anti-liberal impulses.

Now, one of the hallmarks of the “new” right today is that its (mostly younger) adherents bristle at the constraints imposed by those institutions, viewing them as little more than controlled opposition. At the same time, much of this remains more a matter of rhetoric than policy. And their defenses of, uh, looser discursive restrictions mostly end up falling back on liberal precepts.

For example, the other week, Ross Douthat interviewed Jonathan Keeperman, a young-ish right-wing publisher and former Twitter personality under the name “Lomez”—he of “Longhouse” fame. Keeperman argues, both descriptively and prescriptively, for a widening of the boundaries of acceptable public discourse, even up to and past the point of taboos around race and gender.

But Keeperman’s position is in fact the very Mill-ian classical liberal one that it is generally preferable to allow for exposure to a wide range of ideas, and the truer ones will tend to win out in the arena. Now perhaps this is right, and perhaps it isn’t, but either way it does not represent a meaningful alternative to liberalism. It is really a defense of the expression of various positions that might be uncongenial to the sensibilities of most contemporary liberals while still relying on larger liberal assumptions. (I suspect the dirty secret of many people on the nominal “right” today is that they would be perfectly satisfied with a return to the America of the late ‘90s.)

In a more philosophical vein, Patrick Deneen has launched broadsides not just against contemporary liberals but against the larger project of liberalism going back at least a quarter millennium. This certainly sounds like an ambitious alternative, but then it was striking how Deneen was unable to respond persuasively to even mild questioning of this thesis—and let’s be real here, Ezra Klein isn’t exactly Oriana Fallaci.

Trump himself is of course, not conservative but he is also not really right wing either. (It is often forgotten that he frequently mused about running as a Democrat back in the day.) We seem to have difficulty accepting that our present disputes, however intense, resist being classified in terms of conventional ideological categories. It is interesting and perhaps heartening that we persist in ascribing such significance to our political conflicts. We simply do not want to see them in prosaic terms.

But they are largely prosaic—perhaps nowhere more so than in their frequently pecuniary motivations. For example, the New York Times recently ran a long and silly article on a popular streamer named Hasan Piker, noting how he combined various left-wing positions (anticapitalist and anti-Zionist sentiments) with right-wing signifiers (he lifts weights or something—I dunno, I said it was silly). But the really important thing about Hasan (as it is with a creep like Nick Fuentes or a more centrist online figure like Ben Shapiro) is that he likes money and makes plenty of it with his streams. Similarly, ever since Elon Musk monetized Twitter, not a few high-follower accounts have found that Jew-hatred can be a lucrative business. Now there’s something interesting (and not a little Black Mirror-ish) about the appearance of these diverse and occasionally horrible ideological positions being used mainly for monetary gain, but what they are not is a harbinger of great political clashes. They are just the political equivalent of OnlyFans is all.

As above, Fukuyama did predict that the end of history would be a somewhat dreary time, and that we might see essentially meaningless but nonetheless spirited rejections of bourgeois existence (think Fight Club).

But what he didn’t discuss is the possibility that we would simply deny the constricted horizons of modern liberalism and insist that great conflicts were still playing out. Nor is this even the first time since the end of the Cold War that we have witnessed this turnabout. Recall that the shallow optimism of the Clinton ‘90s gave way to the stentorian cadences of the post-9/11 era, which saw much talk of great dangers and great sacrifices. I can still recall as bland a figure as David Brooks giving a speech at my alma mater, in which he suggested that the bold project of democratizing the Middle East could serve as a necessary correction to the anomie and atomism to which liberal democracies like ours were otherwise prone. How young and innocent we were back then.

More lately, the chimerical marriage of technocratic liberalism and eschatological rhetoric that characterized the Obama years gave way to the Trumpian reaction, first in 2016 and again in 2024 (we are now it seems allowed to acknowledge just how much of a placeholder Biden really was). These reversals are undeniably exciting to those experiencing them, but this kind of presentism leads us to overstate their significance.

And in fairness, I am not myself proposing some grand alternative to contemporary liberal democracy—I too am Fukuyama-pilled, you might say. But I think it behooves us to be realistic about where we stand and also about the actually limited scope of both thought and action these days. Our political conflicts are largely a game of dress-up, like children at Purim pretending to be Esther or Haman.

The one partial exception here is the issue of human migration, which is both novel and consequential. It is novel not in total relative share of the population (which crested in America in 1890), but in absolute numbers and scope (e.g., across Europe) and also in the more widely diverse origins of contemporary migrants (please, pretty please, spare me the “how the Irish became white” takes).3

A nontrivial portion of contemporary political disputes revolve around this issue, and these are real and consequential questions of governance—who to let into your country, and what to do with those who try of their own accord? But in the end they are not ones that entail particular political commitments. Rather, they activate certain existing ideological tendencies without cleaving along them in obvious ways. Thus, one can champion open borders for refugees (egalitarian!) or for migrant workers and cheap labor (not so egalitarian!). But either way, this is an intra-liberal debate.

In the end, this question like many others these days—cf. energy policy, business regulation, etc.—is an eminently practical one; states will have to take a position on it as a matter of course. But it is not an inherently ideological one, and the appearance of ideologically charged energies that have coalesced around it and related concerns has had a smoke-and-mirrors effect. It has obscured the more prosaic reality of these political issues, giving them the appearance of grand ideological clashes.

For, the truth is that none of these disputes really corresponds to the political labels we rely on: liberal/conservative, right-wing/left-wing (and forget capitalist/communist). And this is without getting into all the silly excitement over fascism.

What I suspect confuses us is that we have not run out of problems to deal with. But the management of issues like foreign threats or public wealth is basically an unavoidable fact of organized social life. It’s just that doing so does not necessarily cash out in terms of a particular ideological commitment, even though we continue to assign ideological properties to them out of sheer habit.

The dreary reality is that we do not have grand causes; we have petty causes dressed up as something finer, and little that has happened in the past decade has changed that for all its excitement. But it must be said that there are worse things than deluding ourselves into believing these trivial disputes are the stuff of great politics.

And I suppose part of me can’t help wondering if this denial of our true situation is but the last stop before we all go down the long slide into graver displays of decadence, many of which we’re already seeing: increased reliance upon machines to do our thinking for us, declining birthrates, rising acceptance of euthanasia, and so on. This submission to meaninglessness is far worse than delusions of importance.

That Leonard Cohen song had another verse, by the way. Its ends with the line: “I’ve seen the future, brother, it is murder…”

Palestine is also a tricky case on substantive grounds, given the actual orientation of Hamas and PIJ, though this dynamic is hardly unique to Palestine; it is a tension that appears throughout instances of left-wing support for nationalist movements—viz. one can insist that the such causes are definitionally left-wing, but the actual people driving them may have other ideas.

The killing of two Israeli embassy staffers at Washington’s Jewish Museum this past week is apropos here.

Incidentally, this is a lacuna in Fukuyama’s book, which presupposes the continued development of liberal democracies around the globe that presumably end up representing mostly static populations. He does discuss nationalism more broadly but treats it (and the various conflicts arising therefrom) as but another relic of history that will fade in importance, and on this point, I am inclined to think him overconfident. In any case, I think the dismissal of the question of substantial migration among political philosophers is a common one. I can recall asking the political theorist Joseph Carens, who strongly argues against border restrictions, how this would work in practical terms, and his response was basically that most people would be more likely to stay put anyway. Which might be true, but as the Canadian case indicates, that still leaves a lot of people who may decide to come to your country, and what then?

Though I disagree in important places, for instance I did think Fukuyama discussed "the possibility that we would simply deny the constricted horizons of modern liberalism and insist that great conflicts were still playing out" (how else were those new wars for recognition going to play out?), much of this is well-said on an important theme, correcting more mistakes than it introduces.

Tony Judt wrote a book Postwar in much the same vein as Fukuyama which was very sanguine about the eternal peace and prosperity sure to be enjoyed by all after the fall of communism.