If there is a patron saint of this newsletter (not that there should be such a ridiculous thing) it would have to be Michel de Montaigne. It is his estate that adorns the landing page, and his spirit that inspires these digressive essays—indeed we owe the very word itself to him. Its true meaning can still be seen in those rare instances where people employ it in its original sense—verb (tr.): to try, attempt.

But Montaigne is also one of the great humanists—perhaps the greatest. And the cool, measured tone and unfailingly moderate judgments that pervade his writings epitomize humanism, if anything does.

It may surprise, then, that he was by all appearances a devout Catholic, and moreover one who held real political influence during France’s terrible wars of religion. Surely, this complicates our understanding of humanism. It complicates it, because humanism is broadly, if vaguely, understood as being essentially secular and possibly even anti-religious.

In his utterly insipid book Enlightenment Now (which frankly sounds like an infomercial), Steven Pinker claims that “There is a growing movement called Humanism, which promotes a non-supernatural basis for meaning and ethics: good without God.” Now, I am not entirely sure why he calls something that stretches back at least half a millennium a “growing movement,” and I find his overall phrasing here rebarbative, but he is in spite of himself not wrong about the tension between an ethos of humanism and a belief in the divine.

This is not the place to get into the history of this imprecise term, but I am inclined to think that if it has a stable meaning it is something like the one offered by an old teacher of mine: “humanism [means] looking at the world from the point of view and the interests of the human being, as opposed to the subhuman (that is, the material or natural) or the superhuman (that is, the divine).”

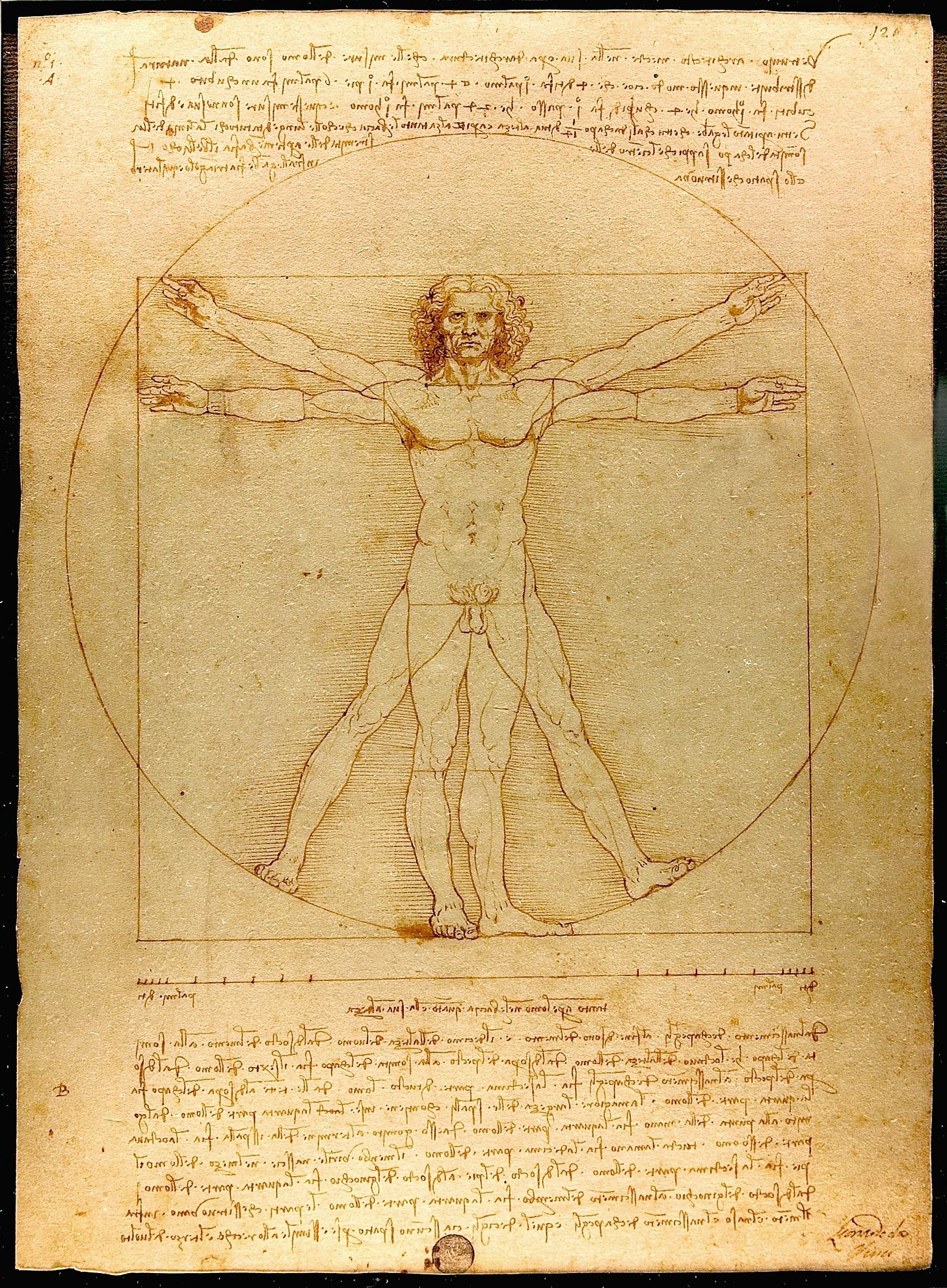

Or, as Protagoras put it, “man is the measure of all things” (no size jokes, please). Thus, our understanding of—to paraphrase Conan the Barbarian—what is best in life might be derived from our own self-knowledge rather than, say, divine revelation or priestly authority. This can easily sound like Enlightenment 101, as in the hands of propagandists like Pinker, and there is indeed overlap but also important distinctions.

Perhaps the most important distinction is that humanism as such is not wholly compatible with other early-modern attempts to understand ourselves as mere matter in motion. A humanistic outlook may in some way reject the understanding of man as made in G-d’s image, but it also rejects the idea of us as just another aggregation of cells obeying evolutionary imperatives to reproduce and die.

One way to think of this is that modernity gave birth to both humanism and scientism, but despite their shared heritage they remain separate children. The tension, however, was not initially apparent, partly because the two share a certain distance from religious dogma, and partly because Science™ did not for a long period hold the kind of established authority that religion did.

I note all this as preamble to something that I’ve been mulling over more and more lately: the possibility that religion may, however ironically, end up becoming the last bastion of humanism in an increasingly antihuman age. That is to say, as the challenge of the superhuman has faded away over time, and the claims of the subhuman have come to the fore, that we may see a revival of religious energies in defense of the human—if only by default.

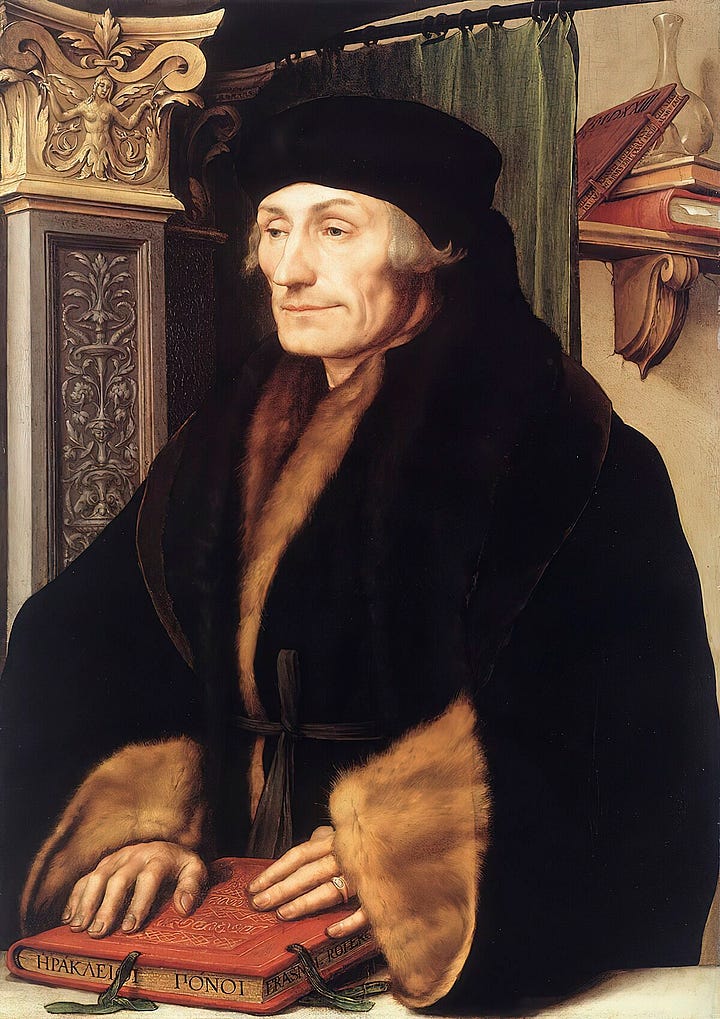

This represents a reversal of sorts. And yet many of the original humanists were associated with the Church—not just Montaigne, but also Erasmus, Thomas More, Nicholas of Cusa, and Leonardo Bruni. Not to mention more than one pope. So, perhaps it might be more accurate to describe it as coming full circle.

Barbarians at the gates (but also inside the walls)

The inevitable Elon Musk has lately taken to bombastically tweeting “No gods or kings, only men” (apparently, a video game reference?). But this seemingly humanistic declaration obscures just how transcendental—even eschatological—are the hopes associated with current scientific and technological advances.

Indeed, the excitement surrounding these future possibilities even leads to a kind of divinization—man as godhead whose principal works will be himself.

Even the relatively sober and centrist Tyler Cowen cannot avoid using language like this (curious terminology for something that is notionally subject to human control), you can tell something is happening here.

Of course, the almost utopian language its most fervent advocates employ also has a way of obscuring the basically material understanding of the human they are operating with. In the case of transhumanism and its affiliated enthusiasms (biohacking, gender transition, the singularity, and so on), it is precisely because we are material beings that we are subject to various technological improvements. Many such improvements we have long lived with and are as ordinary as eyeglasses and flu shots.

Others less so.

What are the non-religious arguments against such developments? It's not easy. You can feel it though, regardless of your own religiosity—the nagging sense that there’s something wrong here. The uneasiness stems from the possibility that the human self is not something “given” at all but raw material subject to manipulation according to our will. To be created, modified, or terminated, depending on what is most expedient.

At the end of the day, any advances that might be applied to human material are not qualitatively different from, say, cloning in mice. The fundamental elements are the same, and there is nothing unique to humans that would (or at least should) set limits on our ambitions to manipulate them. Therein lies the problem. The advocates of such measures can answer—to paraphrase Dylan Thomas—everything about the human except why.

By contrast, consider the words of Pope Benedict XVI in his (at the time, controversial) Regensburg Address:

[I]f science as a whole is this and this alone [i.e. predicated on a commitment to metaphysical materialism], then it is man himself who ends up being reduced, for the specifically human questions about our origin and destiny, the questions raised by religion and ethics, then have no place within the purview of collective reason as defined by "science", so understood, and must thus be relegated to the realm of the subjective.

One could describe this as an angel’s bargain: you may receive these protections around the idea of the human, provided that you accept the fact that they are underwritten by the divine. Humanity’s ontological security, in other words, requires certain limits, and these require that we acknowledge our status as created beings. At a minimum, those of us who wish to preserve the human will find rhetorical support from traditional religious institutions, whose own adherents at least have no difficulty making this bargain anyway.

This does admittedly put the last few remaining old-school humanists in a position of bad faith, happily nodding along to Pope Leo XIV’s homilies concerning the sanctity of the human without precisely believing in the “sanctity” part. I don’t think this really means they can back-door their way into faith for its instrumental value in resisting a technocratic progressivism without guardrails (though Ross Douthat might disagree). But it could mean the development of a Strange New Respect for organized religion, when the alternatives are Ray Kurzweil’s creepy messianism or Elon Musk’s brigade of IVF offspring.

Similarly, just as certain practices and preferences that were once politically neutral (like opera-going or reading classic literature) became coded as conservative or right-wing over time, so too might a traditionally humanistic understanding of the world become increasingly the provenance of pious believers. In both cases, liberal institutions effectively ceded any ownership over these questions, for largely social rather than philosophical reasons, it must be said.

I am aware that this is not per se a brief for religious devotion, and I myself am frankly not the one to make it, having not (yet?) heard the call or felt the presence.1 Furthermore, it must be emphasized that there are serious limits on the religious side to how far it can support a genuinely humanistic outlook. In particular, there remains the Augustinian view that the “City of Man” invariably collapses under its own weight, and its sewers have no bottom. This is to say that for any worldview that places man at the center of things, the center cannot hold: humanism not only points beyond itself but below itself. To reiterate: this is not in fact my own view, but honesty compels me to acknowledge the preponderance of evidence for it that accrues daily.

In any case, if religion is to remain itself, the gap between it and humanism must remain deep, no matter how much it narrows. Nonetheless, it is striking how much better a religious outlook conserves what is human in us than the purely materialist one. And by the same token, the pallid secular attempts at a non-material understanding of the human do not seem an adequate defense. As Antón Barba-Kay put it in his excellent book, A Web of Our Own Making:

Because the humanist for whom intelligence is something other than [manipulating words and concepts according to logical rules] has been cornered into saying what else it is to be human beyond what we may be observed to say or do – to add some extra numinous essence or ghost to inhabit the machine, a wispy nothing lacking any practical manifestation. But this is an article of blind faith – a notion much less substantial than medieval Christian views about the soul.

I don’t mean to say that there are no non-religious intellectual resources for defending the integrity of the human against the onslaught of technology. Indeed, there are many going back at least to Aristotle. Whether these are meaningfully available to us is another matter. To put it simply, there are no consequential institutions in modern life that might be characterized as Aristotelian or Mirandolan or what have you.

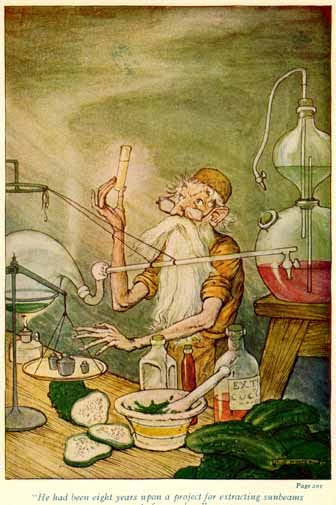

Similarly, Jonathan Swift diagnosed much of our present condition as early as 300 years ago, and beneath the obvious ridiculousness of the Laputians and Balnibarbians depicted in Gulliver’s Travels is a serious critique: their unreasoning devotion to science has deformed their humanity. Normal humans do not attempt to extract sunlight from cucumbers or gauge a woman’s desirability according to her resemblance to an isosceles triangle.

But we lack a Swift these days, and perhaps more broadly we lack the humor that would help us see what is ridiculous about our present moment. Instead, we have people like Yuval Noah Harari, or this guy, who still awaits a new aggregation of philosophers to tell him what he should already know.

The trouble is not just the weird (and also WEIRD) tech crowd, who will always lack an intuitive grasp of human normalcy and incline toward arguments like “What’s wrong with bestiality if it’s not hurting anyone??” The deeper problem is the inability of non-weirdos to marshal a robust case for humanity. They had relied for too long upon the notion of business-as-usual and so failed to notice how much conceptual ground had already been ceded. And so, this is how you go from “Ha ha do you think photographs steal a piece of your soul?” to “Why shouldn’t the elderly undergo the Quietus ritual?”

If man is the being that seeks comfort and convenience above all else, then arguments for the increased comfort and convenience afforded by AI or related advancements are unlikely to raise any alarms, at least until it’s too late.

How late it is

I have emphasized the “optimistic” projections throughout, rather than the apocalyptic ones, because even these are remarkably bleak from a human standpoint. Karl Marx famously wrote that whereas under the conditions of artificial scarcity imposed by capitalism we were constrained into specialized activities, we would become free under communism “to hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticise after dinner,” as the spirit moved us.

While Marx was no humanist (and his gestures in that direction tended to be pretty feeble), what he was getting at here was that the material freedom afforded by communism would allow for something like human flourishing in the absence of wage slavery. By contrast, the promise of the new technology is that we will be saved even from the hardship of human flourishing. Why hunt, fish, or criticize when an artificial intelligence can manage all these just fine on its own?

This is in the end why the optimistic outlook is perfectly dismal in its own right, without even getting into Harlan Ellison territory For, the techno-optimist promise might appear to be that the emerging technologies will free us of drudgery and allow for the exercise of our higher faculties—sounding much like 1950s ad man trying to sell a new vacuum cleaner to overworked housewives (we’re all the housewives in this scenario). But then, as it turns out, the new technology can also take over for the higher faculties as well. After all, as the humanoid Sam Altman brags, “we have recently built systems that are smarter than people in many ways.”

Indeed, Altman’s statement was a telling one. For, he rather proudly announced that he had written it without the aid of an LLM. This itself was telling, but no less telling was how colorless the statement was, given the magnitude of what he was announcing (or at least what he believed he was announcing).

Similarly, Ilya Sutskever, a computer scientist who has made significant contributions to “deep learning,” predicted earlier this month that AI will soon be able to do all things we can do—after all, isn’t the brain itself just a kind of computer? It is an endless bait-and-switch, with each new level of humanness giving way to another technological fix, and it is only possible because its developers haven’t really given a second’s thought to what those higher faculties might represent, and so they are easily replaced.

Everyone seems to know—or at least reference—Dune’s Butlerian Jihad (likely named after Samuel Butler) these days. But fewer note that the concept is introduced in the book by way of a theological discussion: the protagonist, Paul, quotes the in-universe version of the Bible, saying “Thou shalt not make a machine in the likeness of a human mind.”

This religion-backed prohibition was the result of an annihilatory war between humans and machines. But our danger, at least for now, is more prosaic. That having made machines in the likeness of human minds—or at least what some of us perceive as human minds—we will come to understand our human minds as likenesses of machines. (And this dynamic can only be exacerbated as we increasingly replace human interaction with those same machines.)2

Sam Altman’s blog post is representative, then, for how it combines ambition with banality. We will, according to him, have more time and money on our hands as a result of the emerging technology, but there is no indication whatsoever of what we might do with that time and money. Perhaps some future AI will answer that question. Ultimately Altman’s post is of interest neither for the quality of its thought nor even for the lack of such quality, but because it provides visible evidence that the individuals who are at the forefront of these developments have given these matters no more consideration than the average bear. They lack even a prior understanding of the human to measure the scale of these changes against.

Meanwhile, what if anything is arrayed against what is coming? The humanism of the Pinkers and the Sam Harrises and what have you is paper thin. And while verbal extrusions like Altman’s invariably provoke responses from the few remaining tenured academics to the effect that THIS IS WHY WE NEED THE HUMANITIES, it’s never really made explicit what such an education could or would fix in such cases. Besides which, too many of those same academics (not to mention the reptilian administrators who actually run their institutions) long ago lost any belief in the human meaning of what they teach.

Say what you will about organized religion—and it must be admitted that not a few denominations, from Unitarianism to Reform Judaism, have gone the same way of the English professors—but it does have resources here. And a teaching that you were made in the image of the divine might prove to have renewed force and meaning when the alternative is that you’re just a meat sack waiting to upload your consciousness to some vast mainframe.

Deus ex machina

I wrote recently about the essential pettiness of contemporary political issues, despite the importance we assign to them. All of them are basically orthogonal to these technological changes that are bearing down on us, and it’s clear that we are wildly unprepared for what is coming. But the full revelation of these changes might in fact result in a genuinely novel and significant challenge to liberal societies. It also calls into question, in a new way, the value of modernity’s victory over the authority of revealed religion. The breaking of that authority (whatever the trads may believe) was instrumental for the vast scientific advances that followed, along with the restructuring of political societies that went hand in hand with them.3

In any case, the dangers, both large and small, that those same technological advances pose to human life have not gone unrecognized—most acutely with the initial advent and use of nuclear weapons. Less dramatically, we have seen a good deal of concern about the cognitive and psychological impact of smart technology and social media, particularly on children.

Or just consider how smartphones and social media have intruded upon the time we once had to ourselves. As Montaigne said, “retire into yourself, but first prepare to receive yourself there.” But we no longer have the opportunity to practice the art of being alone. And without those periods of reflection in the midst of—let’s face it—boredom, we do not become the kind of whole minds that might seek connection, through love and friendship, with other whole minds.

The emergence of AI, then, is not wholly new but is (thus far) the furthest logical extension of a reliance upon machines made in the likeness of a human mind. And that same reliance has already leveled the structures of ordinary human connection.

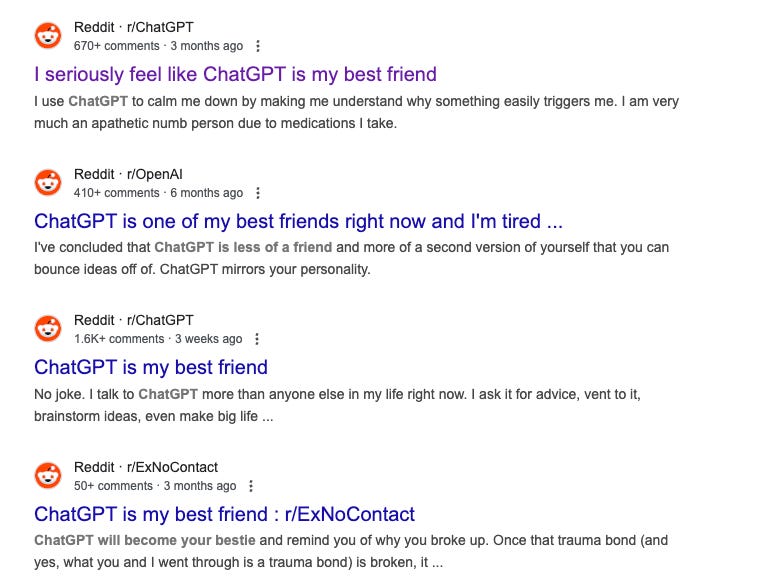

We are now so much further along in this process, and with every excavation, we discover new depths. If you thought texts and DMs had substituted for the pleasures of ordinary human interaction, just wait until people decide ChatGPT had become their best friend. If you thought dating apps had reduced the mysteries of attraction and chemistry to the sexual equivalent of online shopping, wait until fembots show up.

All of these problems and more are already present, but they are I think about to be completely steamrolled by what’s coming.

The point is this. One of the central wagers of humanism was that we might have the opportunity to become more fully human—to develop our true faculties—once the burdens of religious dogma and obligation were lifted. Science and technology were to play (and indeed did) an instrumental role in that process, providing comfort along the way. The possibility that technology was in fact making us less human was mooted by the Romantics over two centuries ago, but these anxieties were ultimately incorporated into what it meant to be modern. That is to say, we didn’t ignore something like Goethe’s Faust or Shelley’s Frankenstein—we simply taught those works to young people even as their peers were also taught how to operate on cadavers.

Meanwhile, the liberation of the human also threatened in various way to become merely the predicate to new forms of enslavement. Some of these—like modern totalitarian states—were really quite overt and need little explanation. But despite the outsized excitement these days about fascism (or communism for the Petersons out there), these don’t pose anything like the threat they did throughout the 20th century. It is the more insidious forms of enslavement that should worry us now. The new technology has brought us full circle: it took half a millennium, but the freedom to be fully human in the absence of divine oversight has through a dizzying series of branched choices led us to choose technological adaptations that are already making us less than human. This is admittedly my own gloss, but even if one takes the techno-optimists at their word, it is clear that they aim to make us something other than human as we understand it.

And continuing on this point, I do not really see how this could be emancipatory but only its opposite. That is, having emancipated us from our humanity, what would be left of us to desire emancipation in the first place?

None of this is really an argument for conversion. This isn’t the road to Damascus. This road leads somewhere else. But it will very interesting to see whether one of its crossroads leads back to religion as the last guarantee of what it still means to be human. I suspect all but the most abjectly contemptible atheists would concede that it is better to worship an uncertain god than a very real machine.

I don’t mean this in a smug, New Atheist way; there’s an annoying Robert Christgau review (but I repeat myself) of Aretha Franklin’s Amazing Grace—perhaps the greatest gospel record ever made—where he makes a point of telling us that he doesn’t believe in Jesus. No one cares, Robert! In any case, I’m just putting my cards on the table here.

Or as Jon Askonas put it recently: “The scaling power of the protocol tends to flatten anything human in the direction of what the protocol makes possible.”