My Music Career

I felt I needed a bit of a break from heavier themes, and this post was inspired by my friend Ryan Floyd of Detached Notes. He has belatedly made the excellent decision to get into vinyl and has been pestering me with various related questions. Responding to these made me realize I had an unusual number of thoughts on the subject of music listening, analog sound, technology, etc. so I set them down here.

As far back as I can remember, I always wanted to just sit around and listen to good music. In my earliest years, which I can barely recall, this would have involved hearing my parents’ original record collection (alas, too sparse to begin with, and too subsequently picked over by my two idiot brothers to be of much use later in life). From there it was cassette tapes; first mainly in my parents’ cars (Graceland and Full Moon Fever featured prominently) and then over time on my own, played out of a tinny boombox that in retrospect resembled the one that got Radio Raheem killed (no Public Enemy in my case, however, at least not back then).1

The subsequent jump to CDs felt galactic at the time. That shiny aluminum-coated polycarbonate, the way you could skip entire tracks with the push of a button, the fact that it used frickin’ laser beams. Plus, as everyone knew, these were digital—occasionally advertised as “digitally remastered”—a fact that was vaguely understood to indicate technological superiority in the same way that the residents of a future America in Idiocracy understood that plants needed electrolytes.

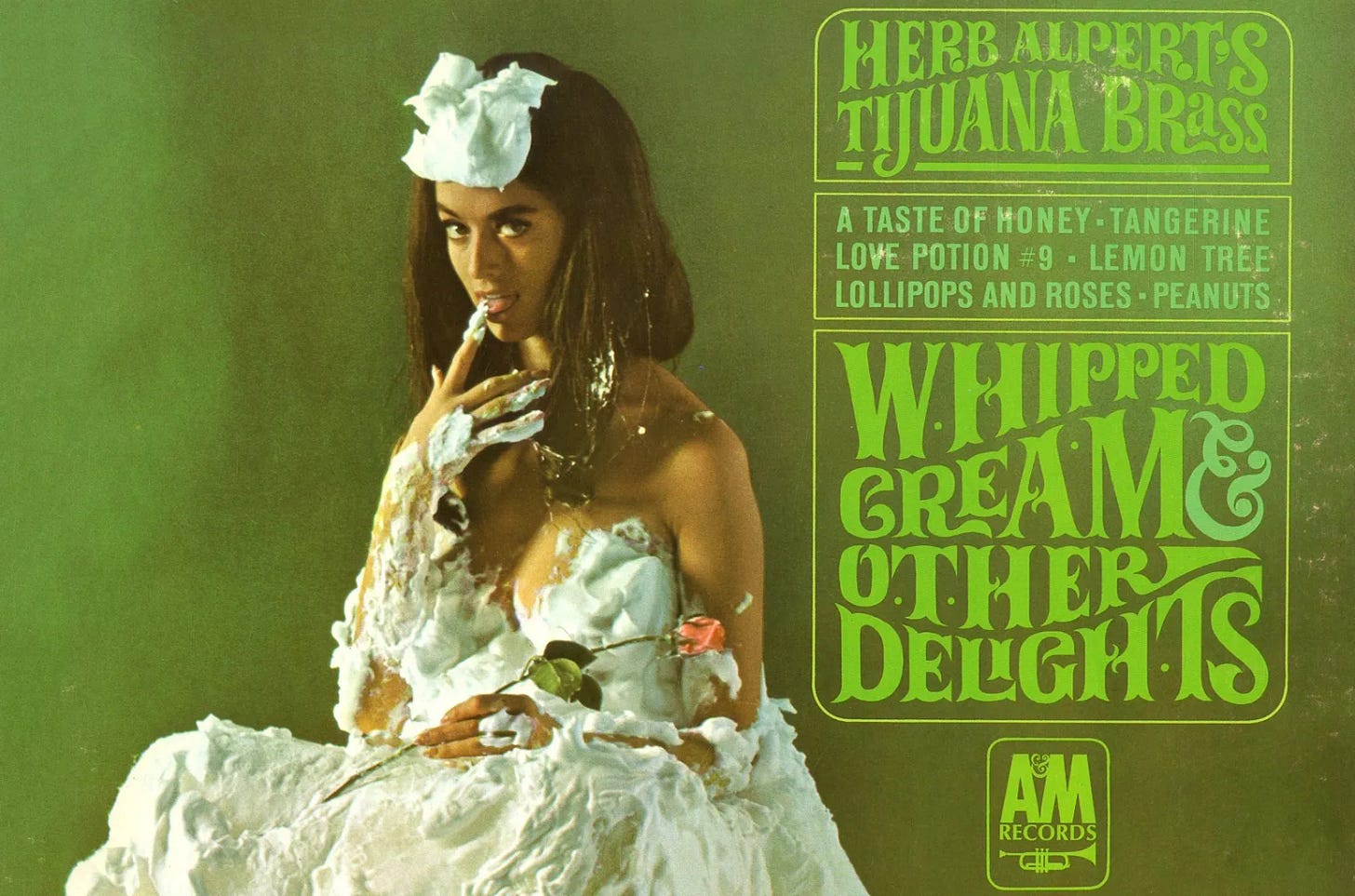

As those same digital CDs were supplanted by digital streaming in the first decade of the present century—replacing a flimsy contrivance with something altogether immaterial—things began to come full circle with the return of vinyl. This was an interesting period during which it was clear that much of the vinyl revival was driven by the idea of vinyl more than the reality. That is to say, records—often kitschy ones, like Herb Alpert’s Tijuana Brass—seemed to be part of a demi-generational gestalt that prized all manner of anachronism: pre-Prohibition cocktails, guys sporting spats and Civil War-era facial hair (often the same guys making the cocktails), drinking out of mason jars (again, for the cocktails), etc. A lot of it in retrospect was a kind of concession to a harsher reality following the economic crash: finding consolation in cheaper things.

My own case was more specific. When I moved to Toronto to pursue a PhD, I finally got the thousands of CDs I’d amassed back out of storage after years of gallivanting around the world. In an O. Henry-esque development, my now-wife bought me a turntable for my birthday, and I started selling off said CD collection to finance an engagement ring (which is how she became now-wife). Naturally, part of the process of selling the collection involved taking a handful of records here and there in trade alongside the cash.

Right off the bat, however, I began to notice a qualitative distinction in sound when playing those records, which in turn got me thinking about sound in general and what it means.

The medium is (sort of) the message

There’s a lot of pabulum written about vinyl records: the “ritual” of removing the record from its sleeve and lowering the tone-arm and really mindfully listening, man, and all the other details that people should really get their keyboards taken away for writing about. It’s not that isn’t true in some sense, but it swiftly crosses the threshold between legitimate appreciation of the physicality of our world and egregious fetishism.

It’s not that I don’t indulge in it myself, but what always interested me most was the sound. Here I should probably note upfront that I was born mostly deaf (yes, I’m aware of the irony—see here and here for more on this). In retrospect, it’s probably odd that I should have gone almost three decades without really thinking that much about sound, when it (or its absence at any rate) was obviously central to my existence. Granted this was probably healthy in a lot of ways, but it wasn’t so much a psychological disposition as an epistemological one. That is, I didn’t really perceive that hearing aids were mediating my experience of the world. As far as I was concerned, what I was hearing was sound.2 Over time, however, I couldn’t help but notice psychoacoustic differences that complicated this understanding—the way that sound could change across different hearing devices, or in different climates, and so on.

Suffice it to say, it was a fairly natural progression from there to take a greater interest in the other components that shaped the music I was hearing, particularly once I started buying LPs. Why, for example, did a late ‘60s pressing of Coltrane’s Ballads I’d come across in a Queen West record store sound so rich and alive compared with what I’d been streaming for years—or for that matter compared with a brand-new reissue of A Love Supreme I’d been gifted? Why did it seem qualitatively, dimensionally different in a way that felt subjectively meaningful?

One answer is that it was in fact dimensionally different.

Quick and dirty explanation: strictly-speaking, there is neither “analog” nor “digital” sound. A far as we humans are concerned, sound = sound waves, which you perceive as sound via your ear drums, auditory nerves, brain, etc. If I were explaining this to you at a bar, you would simply hear the sound waves produced by my vocal chords. But if you got home later and for some reason still wanted to hear my thoughts on sound, you’d need a way of recording and then playing back my voice.

What we call “analog” is one way of doing that. In the case of vinyl records, those sound waves are cut in microscopic form into a master which is used to press the records you buy. Those waves then gets traced by the stylus on your turntable (those tiny grooves it tracks being the rendering of those sound waves) and amplified many times over by your amplifier and driven out through the speakers. Those grooves are literally an analogue of the sound wave, hence “analog.”

Digital audio, by contrast, has to render that same information as 1s and 0s (as it does all information). Higher-resolution streams will feature more 1s and 0s—that is, more information—and lower ones fewer, which means you’ll hear less music when the track is played back, which is another reason why Spotify is bad. (There’s quite a bit more involved w/r/t resolution, but let’s leave it at that for now.) In any case, digital information needs to be recoded as analog before it can be driven out of the speakers and reach your ears as sound waves. The DAC (=Digital-to-Analog Converter) is the mechanism for doing that, and you have one in your smartphone, computer, car stereo, etc., just as we used to have them in our CD players. The better and more sophisticated the DAC (especially given a reasonably high-resolution source), the more naturally musical and true and non-fatiguing the sound you hear will be.

As it happens, that unengaging pressing of A Love Supreme I mentioned turned out to have been cut from a CD (digital) master rather than from the original tape. Something had been irreversibly lost in the process, and you could hear it in the end product. By contrast, that vintage version of Ballads retained a kind of direct connection to what John Coltrane’s quartet had played in Rudy Van Gelder’s studio all those years ago.3

But there’s something else going on here as well.

Neal Stephenson (yes, that, Neal Stephenson) has a remarkable essay on the invention of the personal computer called “In the Beginning Was the Command Line,” in which he makes the perceptive point that modern technology renders much of our experience metaphorical. For example, the graphic user interface that virtually all of us use (and that I am using right now as I type this) is a kind of metaphorical representation of the computer’s actual underlying processes that run the programs we use and deliver the outcomes we need. Or just consider the difference between the word “document” (or “DOC”) as used for things like text files on our hard drive and what it actually means to “document” something.

This kind of metaphorical relationship with the phenomenal world has consequences. Stephenson describes one of them as “metaphor shear,” i.e. the moment in which the limitations of that metaphor’s ability to describe reality is suddenly and often unpleasantly revealed. Rebecca West remarks somewhere that, despite being a highly educated woman, her understanding of so much of the world around her was not much greater than that of a superstitious peasant—indeed, it may be poorer, seeing as the superstitious peasant at least derives poetic meaning from the belief that a river spirit inhabits a waterfall, whereas she does not even get that from the awareness that something called “physics” has to do with why bridges stay up and airplanes fly. And don’t tell me your own understanding is vastly superior a century later. Quick: explain to me how CDs work (and don’t say “lasers”).

All of this is obscured by something like a Bluetooth speaker. It’s not just that such a device sounds shitty (though it usually does), as that it removes us from the means by which we play back recorded music. Alexa has only made this worse, because we can simply issue verbal commands for it to play what we wish to hear—like Aladdin to the genie—and sound emerges from the same speaker-box itself.4

It’s difficult to even think about questions of sound quality, when the mechanism that provides us with sound is so remote (this is not unlike the way that Apple has consistently made a point of producing hermetically sealed products so as to limit our interaction with them to their outputs). We have no particular sense of the location or nature of the music’s source, nor the route it travels before we hear it emerge from the tiny speaker. This, in combination, with the impossibly voluminous libraries (abstractly-speaking, of course) of digital music and ease with which we can access them, renders the whole business queerly unsatisfying. Or, if not, unsatisfying, then somehow weightless and inconsequential.

Vinyl, meanwhile, induces quite the opposite sensation (just try carrying a full moving box of records). One is confronted always by the sheer physical weightiness, requiring crates and shelving units and dividers, and that’s without getting into audio gear and equipment racks. Obviously, one can turn this into a fetish, and for many people a record functions more as an objet d’art than as a medium for music (a non-trivial amount of the record business is presently being propped up by teenage girls without turntables buying Taylor Swift LPs—this is not a joke). Nobody should want to become this guy:

Nonetheless, analog sound reduces some of the metaphorical distance Stephenson describes, allowing us to again perceive sound as a part of the physical world we inhabit.

The Audio Thing

There is in my observation a robust but non-deterministic correlation between vinyl types and audiophile types, though the most serious collectors I’ve come across tend to have fairly basic systems. I chalk this up to a combination of scarcity of resources both material (money spent on expensive gear is money you’re not spending on rare LPs and vice versa) and cognitive (most people have a limited fund of attention and intellectual energy, and having multiple obsessions stretches it too thin).

But I suspect at least some of this speaks to an underlying disposition of character: these are simply different human types, whose obsessions happen to converge on the general theme of music-listening. It’s not just that the guys in, say, High Fidelity don’t have the cash for Wilson WAMMs (who does?); it’s that they were never going to be the kind of people who would have that level of disposable income in the first place—and not just because they’d spent it on old Stax/Volt 45s.

Conversely, most of the audiophiles I’ve met either skip LPs altogether or are largely content to buy reissues rather than spend their weekends trawling through dusty crates or estate sales.

The audio thing is interesting, because it both reflects and goes beyond a general democratic antipathy toward elitist snobbery. That is to say, the idea that some things (especially expensive things) are just superior to others, and relatedly that some people are capable of greater appreciation for such superior things just offends us on an intuitive level. But as Kingsley Amis pointed out in Lucky Jim: nice things really are nicer than nasty ones. And this goes for wine, food, couture, architecture, you name it.

But the existence of high-end audio and its appreciators seems to annoy people even more than, e.g., wine and oenophiles. I’m not entirely sure why, except that perhaps it’s more general. Not everyone drinks wine or even any form of alcohol, but virtually everyone listens to music in some capacity. True, there are people who just seem not to feel strongly about it. Back in the CD era, you would see people who owned maybe 10 CDs, all of them “greatest hits” albums. Or the ones who would go and buy a CD at Starbucks (Norah Jones maybe, or a fake mood compilation with a title like Jazz for Hate Crimes) because it was next to the register, after not having bought one in years.5

In any case, I’ve never been able to understand such people. Being indifferent to music seems to me like being indifferent to sex—except of course such people also exist (and in increasingly large numbers if the reports are accurate…). But even beyond such unfortunate souls, the rest of us are in an ironic state: we have instant access to a greater library of recorded music than has ever before existed, and we persist in listening to it in the worst possible way: heavily compressed audio streams piped through cheap plastic earbuds or smartphone speakers.6 It is the equivalent of foregoing a visit to art museums because we can always look at pictures on our phones (which we also do), or having AI summarize books to save us the trouble of reading them (which we also do) and so on.

This seems to be a recurring theme here, but it does seem to be the case that whereas technology was formerly an aid to enhancing human experience, it more and more just overwrites that experience entirely. Like the ant that thinks the puddle is an ocean, one envisions entire generations that just suppose this is what music is supposed to sound like (or that Netflix movies are what cinema is supposed to look like, etc.) I genuinely don’t understand this. Though I suppose there’s a lot about the modern world I don’t understand. As Ray Davies said, “this is the age of insanity.”

The point is that while I get that audiophiles are annoying—a bunch of people talking about things like “timbre” and “sibilance” and “holographic imaging” instead of whether the songs are any good—it’s not a bad thing in principle to care more about the quality of human experience. And in any case spending money on better speakers is certainly no stupider than the money I already spend on dishwashers, refrigerators, and what have you.

Interestingly, most of the really successful (and also good) music out there actually tends to sound pretty fantastic as well. The Beatles, Dylan, old Motown singles all leap out of the speakers. Nearly every great jazz session of the 50s and 60s is at least competently produced, and many are astonishing.7 It’s not incidental that Dark Side of the Moon, Rumours, Thriller—three of the best-selling albums of all time—are all sonic masterpieces. In other words, without being conscious audiophiles or anything, normal listeners innately responded to music that was not just great but great-sounding. (Great sound is also interesting for being unexpectedly varied in its associations: yes, you get it from studio slicksters like Steely Dan or Fleetwood Mac, but you also get it from the Grateful Dead and Neil Young, guys who otherwise look like—and I mean this in the nicest way possible—drunken hobos.)

My own view here is that music provides a kind of patch-through access for emotional connection. Better sound just gives you higher-level clearance—it’s more likely to make you tear up, make the hairs on the back of your arm stand up, make you want to jump around the room like an idiot, and so on.

And as with wine, scotch, etc., these things tend to be logarithmic, by which I mean that one has to spend at constant rates to achieve increasingly marginal gains. This may sound pessimistic, but in fact it simply means that you can get the majority of sonic improvements you’ll ever see pretty much upfront provided that you’re willing to spend even a fraction more than the vast percentage of people ever bother to on your stereo system.

In any case, to repeat Amis, nice things are nicer than nasty ones, and I am happy to be a proselyte for nicer things where music is concerned. Maybe that means spending a bit of what you already spend on cars and fridges and dishwashers for something that brings great joy and pleasure, or maybe it just means taking more time to focus on the music you’re already listening to (and for the love of Christ not giving your money to Spotify).

Ok, it’s not just about sound

I’m not going to quote “Ozymandias” at you, but we are such a wealthy civilization, and yet one wonders just what will be left of us. For, we’ve been poor stewards of our cultural inheritance. We’ve digitized vast libraries only to allow those archives to fall into ruin (figuratively). But the keepers of priceless master recordings have also exposed them to more literal ruin, as when Universal Studios failed to protect at least 120,000 of them from burning up in the terrible 2008 fire (and then covered up the full extent of the damage for years).

To this day, a vast quantity of foundational early-20th century American music—folk, blues, country, zydeco, old-timey, jazz, etc.—remains available primarily or exclusively thanks to JSP Records, a British label that is basically just the brainchild of one mad enthusiast, who oversees digital transfers off of old shellac 78s. (It is, for example, still the best option for anyone looking to acquire Louis Armstrong’s Hot Five and Sevens sessions, which have a strong claim to being the most important American music ever recorded, full stop.)

It is thus remarkable how dicey the business of ensuring that physical copies of this heritage still exist really is. The vinyl revival itself has been a process of fits and starts. When I first started collecting, newly-pressed LPs could still be had for cheap, but it was also clear they were made just as cheaply. The jacket photos were quick photo jobs; they were often cut from a CD copy, as these labels were able to pay enough for limited reissue rights but not enough to actually get access to the master tapes. A number of now-defunct cheapie labels quickly became notorious for this. (Interestingly, many of them had solid musical tastes, which is why it suddenly became easy to pick up crappy copies of killer albums like Marquee Moon or Lô Borges.)

Aside from the economic factor, though, was the competence and infrastructure problem. That is, after vinyl sales (and thus manufacturing) declined, a lot of factories went offline or got repurposed. During the early years of the present century, given renewed inventive to press records, factories had to quickly come back online or get re-repurposed, often by people with limited experience of quality control in this specific area, and thus records from that period were rife with pressings problems.

Similarly, even aside from the question of getting access to the master tapes or the willingness to oversee a complete analog chain remaster, there wasn’t some surfeit of guys with significant experience and skill when it came to the cutting process just waiting to be awoken out of cryosleep or something.

The recovery of this infrastructure and technical experience was not a simple matter. Exceptions remain, like Gillian Welch and David Rawlings, who were crazy enough to acquire their own cutting lathe(!) so that they could oversee the full production and mastering chain for their analog records. But a) this is something few musicians have the will and the interest to undertake; b) it has obvious bottlenecking issues (in that they cannot be expected to make producing vinyl their full-time job); and c) such a bottleneck is easily exposed to externalities, like the hurricane that destroyed half their studio, which admittedly sounds like something that would happen in a Gillian Welch song. Consequently, they’ve had to delay reissuing their masterpiece, Time (The Revelator), on vinyl, and by this point I’m only slightly more anxious for that one to come out than I was for the birth of my second child.

Caring for this heritage is, to my mind, like caring for our major monuments. And while it’s all good to admit certain items into the Library of Congress, this does only so much good if copies don’t circulate for ordinary people to listen to.

Putting real resources behind keeping some of greatest music in print (not to mention doing it right), matters. The right honorable Chad Kassem has admitted that there are certain records he’s been prepared to reissue with zero expectation of turning a profit, simply because he considers it a matter of importance that they remain available. Similarly, the story goes that when the great producer Joe Boyd sold his production company to Island Records, he had one stipulation: that Nick Drake’s records never go out of print—and back then no one was buying Nick Drake records.

The point is: one worries here that we are becoming (at best) dedicated curators of a vanishing culture. Meanwhile, those who might otherwise contribute to its perpetuation are starving in the midst of plenty. I don’t want to overstate the case here. Collecting and listening to music is not a heroic act. But shoring these fragments against our ruins is not nothing either.

To that end, herewith my advice for the novice record collector:

Source and mastering

Possibly the most important criteria in buying new vinyl. The majority of new vinyl available for purchase is still cut from digital sources or masters. This is typically because a) you’re listening to contemporary music, and there are virtually no musicians today with the interest and/or the resources to both record to analog tape and oversee an end-to-end process; or b) you’re listening to a reissue that was either sourced from a digital file or cut from a digital master that was made from an analog source.

There are often perfectly good reasons for this—e.g., the Grateful Dead (or their company, at any rate) continues to put out very good-sounding official releases of past concerts, the board recordings of which are likely not in the greatest shape. Converting the recording to high-resolution digital files and then mastering it in that format, allows for much greater flexibility while preserving the underlying tape. Plus, of course, there are plenty of good albums out there that, since the mid-1980s or so were recorded digitally to begin with.

Before everybody gets mad at me (again), I’m not completely disdaining digital recordings or playback. There are crappy-sounding analog recordings and fantastic-sounding digital ones out there. The point is simply that records cost money, and money doesn’t grow on trees. The added value that vinyl records provide tends to be diminished (IMO) by the introduction of a digital element in the mastering chain, especially when one can now stream high quality recordings for less than the cost of a single new LP per month.

Fit

Vinyl can be an unforgiving medium, but this doesn’t mean it only works for a Blood on the Tracks or Revolver, where every track is cosmically great. Howard Hawks once defined a good movie as three good scenes and no bad ones, and this is sort of how I feel about good records.

You can get a great deal of mileage out of an old LP with few standout tracks but no bad ones—in many ways more mileage than an otherwise great LP with a couple of bum tracks. Records that sustain a strong “vibe” (I hate this word too, so substitute “mood” or “sensibility” if you prefer) across two sides are much to be treasured. This is why albums like Taj Mahal’s Mo’ Roots or Terry Reid’s River or Aretha Franklin’s Spirit in the Dark or JJ Cale’s Naturally, (I could go on here) have gotten so much airtime in our household.

Weight

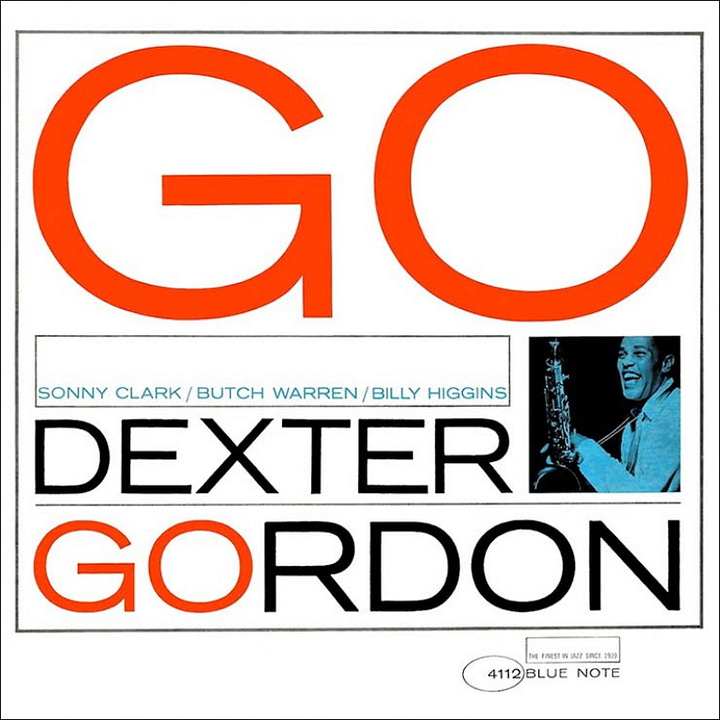

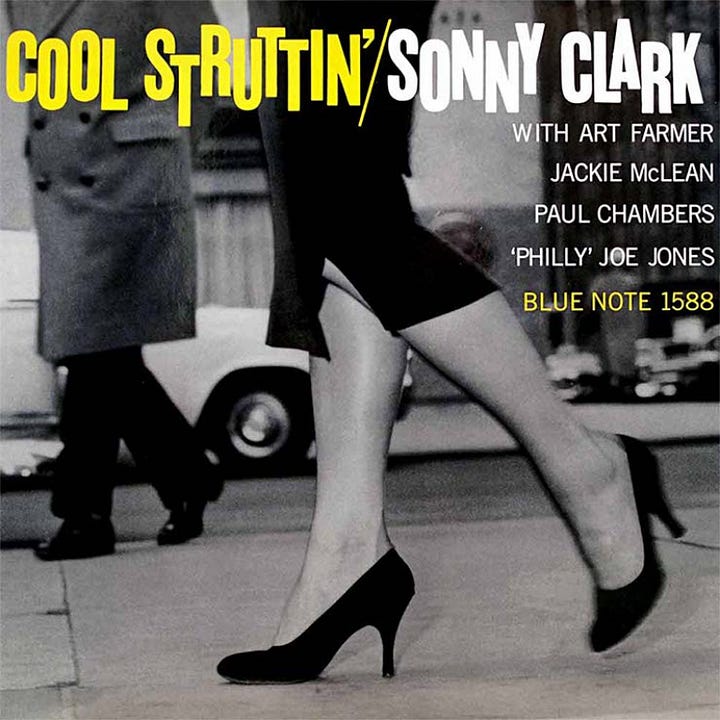

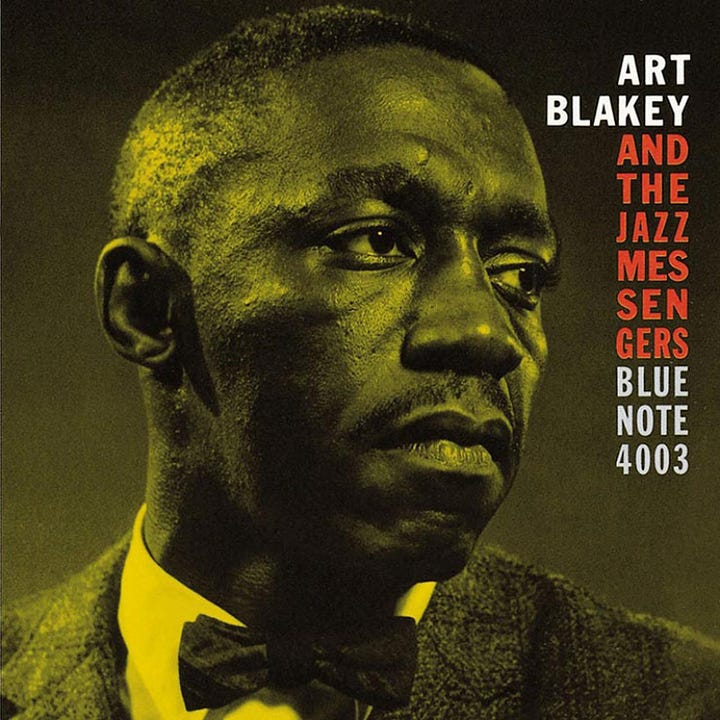

Heavy makes you happy, as the song goes, but it’s not essential. True, one is always impressed by the sturdiness of vintage vinyl. Those old Blue Notes from the original Plastylite factory feel satisfyingly weighty in the hand, and the jackets still look glossy and beautiful and, well expensive.

I don’t want to overstate this, because most of those musicians weren’t living in luxury or anything, but the quality those pressings exude seems like an expression of imperial grandeur—or at least of postwar national confidence. As though tracking our geoeconomic fortunes, vinyl became perilously thin by the mid-70s, thanks to shortages associated with the oil embargo. And of course, after that, its sales were steadily eclipsed by cassette tapes and compact discs.

We are no longer living in an age of uncertain austerity but rather one of abundance, or so they tell me. And from the beginning of the vinyl revival, it was common to see “180-GRAM” stickers proudly emblazoned on reissues of otherwise middling quality. But the actual weight of the vinyl has little to do with the music—the grooves are where the music is, and more grams doesn’t add anything to the grooves themselves. I’ve heard great-sounding LPs that you could practically see through, and dull ones that felt like a brick. That said, ceteris paribus, heavier is still preferable: it’s more durable, less subject to warping, and generally quieter, thus improving the noise ratio.

Turntables

We are thankfully past the kitsch era of the vinyl revival, in which every Urban Outfitters could be seen selling cheap Crosley record players that were mostly good for chewing up records, and today there are a number of very good “starter” turntables available (meaning they’re not too expensive, and they play well, and you don’t have to be an engineer to set them up). Nonetheless, a good rule of thumb when buying your first turntable is that if you could spend roughly the same amount on a few new LPs, odds are against it treating those LPs very well. Also, for Pete’s sake, don’t bother getting one with “Bluetooth capability,” because really what’s the point?

The 45 thing

It’s increasingly common for albums to be reissued in “45-rpm” format.8 The annoying practice of converting what were traditionally 33s to 45s is done because technically 45s, by featuring less music per side, avoid the inner groove distortion associated with 33s (i.e., as the tonearm starts to track closer to the center of the record, certain sonic compromises start to set in). My own view is that any minor sonic improvements are negated by the interruption of the natural flow of the album, not to mention the bother of having to get up and flip the record twice as frequently, but de gustibus as they say. The main point: don’t be shocked if you end up with a double-LP 45-rpm version of an album because you didn’t look closely at what you were buying.

Geography

Allowing for exceptions, country of origin tends to be your best bet for original pressings. British Parlophone mono pressings pretty much smoke anything else you might find for The Beatles. The same goes for Brazilian pressings for Tropicália and MPB, or UK Island and Transatlantic pressings for British folk stuff like Fairport Convention and Pentangle.

Some people swear by Japanese pressings for classic jazz records, but they’ve never done much for me. Ultimately, your ears (and your degree of autism) have to guide you. How much better is the best pressing than the next-best one, and what’s it worth to you in either time or money spent to acquire it?

Res ipsa loquitur

Enjoy the basic practice of holding onto something material and solid amidst so much ephemerality. There is something talismanic about them. Sometimes I get almost dizzy holding them, reading the faded notes on the rear jacket or inside the gatefold and wondering at the chain of ownership that brought something made before the Moon landing, before the Kennedy assassination, or the construction of the Berlin Wall into my hands. Sometimes you get a faint, not-unpleasant smell of minor water or smoke damage.

There’s a scene I love in the excellent Danish film Another Round, in which a group of aging friends who have putatively rediscovered the joys of being kind of drunk, are drinking Sazeracs and listening to The Meters together.

I like the awkward dorkiness of these guys trying to move in time with the music (in fact, Mads Mikkelsen himself is a graceful, professionally-trained dancer, and the film makes good use of his talents in that area). But I mostly like how it portrays the dawning realization that they’re experiencing unfamiliar joy.9

After all, well-made records just sound alive, and listening to them makes you feel alive, in a way that is increasingly rare in a world that seems to becomes more flat, sterile, dead-souled, and artificial by the day.

Perhaps needless to say, making my own purchases initially resulted in a reduction in music quality. I can still recall that around the time I was maybe 8 or 9, my mother overheard me listening to Vanilla Ice and decided that it was wholly inappropriate and confiscated the tape, at which point my dad tried to mollify me by replacing it with The Beatles’ Rubber Soul, in a futile attempt to bridge the generational divide that went unappreciated by yours truly.

This meant, among other things, that I didn’t spend too much time getting caught up in epistemic anxiety, of the sort we associated with adolescent potheads who, upon over-inhaling, suddenly fear that what they perceive as the color blue might in fact be a totally different objective color than what the rest of the world means by “blue,” and they’ve been unconsciously spending their entire life in a cocoon of subjectivity, etc. etc.

I should note here that even analog signals undergo a certain transformation, as it isn’t sound waves that move through amplifier circuitry or speaker wire, but alternating electrical current, fluctuating in accordance with the original signal’s waveform, which is only then converted back into sound waves through the vibrations within the speaker cabinet. This stuff is frankly just weird.

We have allowed our children Alexa speakers for their own music listening, and my refusal to even dignify the robot by addressing it is a source of much hilarity to them.

You can mock such people, of course, but don’t underestimate their market significance; the all-time bestselling albums reached their pinnacle by some mysterious ability to break through to such consumers. People who barely set foot in a record store nonetheless owned copies of Santana’s Supernatural.

A friend who was over my house recently commented how hearing music played off a record through proper speakers, or for that matter live music, now sounds almost eerie; the unreality of most media today becomes its own reality.

Alas, exceptions exist—e.g., Coltrane’s My Favorite Things.

Leaving aside those old shellac 78s, which are their own kettle of fish, records spin at either 33 or 45 rpm (=revolutions per minute). As 45 times a minute is obviously faster than 33, the record ends much sooner, so there’s less music per side. This is also why 45s were historically used for singles back when singles were a real thing. By contrast 33 rpm is the standard for full-length LPs (see why LP is short for “Long Player” now?).

I recognize that part of it is that they’re happy to be day drinking.

This piece was really thoughtful. Made me consider the similarities and differences for books vs kindle. And for the first time I actually want to get vinyls — if only to make sure my children can listen to bangers even if spotify vanishes from the surface of the earth

Three things: very interesting piece even for a former pro musician (and not just music lover) who probably spent more time in music studios surrounded by music equipment, Space Echoes, John Lennon‘s actual mixing desk of the Double Fantasy sessions (bought by a millionaire‘s hyperactive son who built a studio that we recorded 2 albums at), listening back on 6 various speakers - which you could have maybe expanded on: speakers! - and headphones (!) than in any school or university in her youth. Your music writing even for Café Américain was always great fun to read, because it had nothing to do with Lester Bangs/Greil Marcus-style “music journalism“ but with true music fandom. Which then of course made me wonder why you never seemed to care about playing music yourself.

2) you love the “analog” musicians - you almost exclusively mention people who actually played their instruments - but I wonder where electronic music, anything from Pansonic to sub-bass sounds from early drum’n bass to minimal techno (Kompakt etc.), Jeff Mills, or, say, French House (to comb through my personal electronic music history) stand for you.

3) You need an editor.